Ottawa, we have a problem

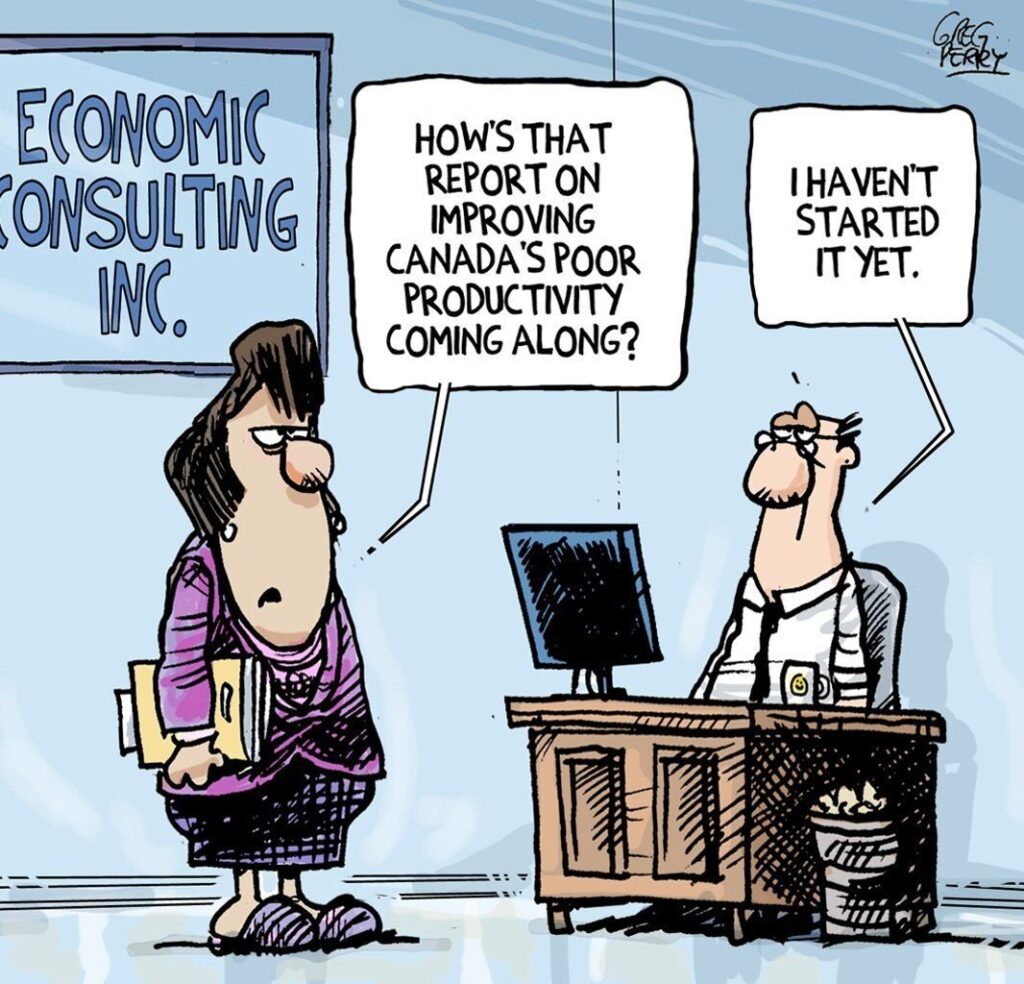

A few weeks ago I saw a story about Canada’s woeful and declining productivity. I manfully resisted the Boomer temptation to blame it on the millennials, and resolved to try to discover what lies behind this phenomenon. I got distracted for a bit by the elections and the orange idiot and things like that. But I’ve had a chance now to look into this issue. It’s an interesting and perplexing problem. Stick with me, and I’ll try to explore its complexities for you.

I’ve relied heavily on articles from the Bank of Canada, TD Bank, and the University of Calgary. You’ll find the articles listed at the bottom. I’m not going to try to identify sources of individual quotes or statistics – if you’re hungry for details, you can read the referenced articles for yourself.

The economists unanimously agree that we have a serious problem:

- It’s a long-standing and persistent problem (“Back in 1984, the Canadian economy was producing 88% of the value generated by the US economy per hour. But by 2022, Canadian productivity had fallen to just 71% of that of the United States.”)

- Our productivity deficit is not just in comparison to the US. (“In fact, Canada trails not only the U.S. but all advanced countries in Northern and Western Europe, as well as Australia . Canada is sixth out of the seven G7 countries, and lags even countries such as Spain or Italy”).

- The problem’s getting worse (“Canadian labor productivity has reversed course in the years following the pandemic, declining consistently over the past three years.”)

The answer is not simply to make those millennials work harder. The productivity measure under discussion is a measure of value added per hour of labour input. So, working longer and harder hours might increase GDP because we’d produce more stuff, but it doesn’t improve productivity because we worked more hours to get there.

Canada continues to experience economic growth as measured by output (GDP). But that economic growth has been “entirely attributable to increased labor hours”, either as a result of increases to the average work week for employees, or increased participation owing to population growth. The result of lower productivity is a lower standard of living. We’re told that “Canadian’s standard of living, as measured by real GDP per person, was lower in 2023 than in 2014.” Increased national productivity would enable real wage growth, more government tax revenues, improved public services, and a strong and resilient economy. It’s seemingly self-evident – if we can be more efficient and productive with each hour worked, we’re likely to be better off, aren’t we?

So, how do we do that?

Well first, the economists break the problem down to bite-sized pieces. I’m going to try to sum up the problem statements as quickly as possible because I think the really interesting and perplexing issues are tied to the possible solutions and I’d rather get to those. So, as a simple listing of problems:

- Construction has generated no productivity growth over the past forty years. Residential building construction is especially weak.

- Manufacturing and agriculture, along with construction, are the weak performers in the “goods sector”.

- Mining, plus oil and gas extraction have been good productivity performers in the past, but have fallen off since the pandemic. In many cases, the easy sources for minerals, oil and gas have been tapped out, so productivity is dropping as we go after the more difficult reserves.

- The “Goods” sector of the economy is shrinking, and “services” are increasing. Service sectors “have consistently and significantly lagged the U.S. over the past two decades.”

- Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador have the highest productivity, thanks to the oil and gas industry.

- B.C., Ontario, Quebec and Manitoba are slightly below the national average

- The Maritime provinces have productivity levels 25 to 31 per cent lower than the national average.

Productivity improvement is seen by the economists as a three-factor process. The first factor is labour force quality, which is an assessment of the skills, training and experience of the workforce. The second factor is capital intensity, which is about equipping the worker with better tools. And third is what they call “multi-factor productivity” which accounts for how efficiently the workers mesh with the tooling, the market, the resource availability etc. I think of it as a measure of the synergies being realized within the business. So, let’s look at thing from the perspective of those three factors.

Labour Force Composition

The labour force in Canada is rapidly expanding as a result of robust immigration. And many of those immigrants are highly skilled which ought to be driving productivity increases. But we are not realizing the expected productivity gains because “it is not clear that employers recognize the value of their credentials”. Many highly skilled immigrants are stuck in low paying, low productivity jobs. The higher their qualification, the higher the wage gap in Canada between the immigrant and their home-grown counterparts. So, we need to boost the opportunities afforded to immigrants, and help them become truly productive.

Capital Intensity

This one is easy to summarize. We’re just not attracting enough capital investment dollars for “machinery, equipment and, importantly, intellectual property.” In the past fifty years there has been “a persistent gap between the level of capital spending per worker by Canadian firms and the level spent by their US counterparts….worse over the past decade… While US spending continues to increase, Canadian investment levels are lower than they were a decade ago.

I have previously lamented the decline in scientific research in this country. Canada’s R&D spending has declined from a peak of 2.02% of GDP in 2001 to 1.55% in 2022.

So why don’t corporations invest aggressively here? The Senior Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada says “biggest concern in this area, I’d say it’s competition. Simply put, businesses become more productive when they’re exposed to competition.” Competition in Canada is inhibited by the vast distances and sparse population, by inter-provincial trade barriers and by explicit barriers to foreign entry in sectors such as airlines, banking and telecommunications. She goes on to advise that there is a documented statistical link between decreasing competition and declining investment.

Another element in the investment calculus is the tax environment. One job of government is to create an environment in which corporations can flourish. So, while some amount of corporate taxation is desirable, there are practical limits to be applied. Canada had created a competitive advantage for companies in the early 2000’s, with lower corporate income taxes, but that advantage has been eroded sharply as other countries have lowered taxes. That is especially true of the deep tax cuts in the US promulgated by the first Trump administration.

A third component of corporate reluctance to invest heavily is a regulatory approval process that can be both lengthy and unpredictable. Our environmental assessment system, our residential and commercial building permit systems, and lack of interprovincial harmony on regulations are all impediments to investment.

Multi-Factor Productivity

Remember that productivity losses because of this factor would be those things that would cause us to be inefficient in adding value even with a skilled workforce and a decent level of capital investment. They include:

- Small businesses. Canada has lots of them, especially in the Construction sector, where 40% of companies have fewer than 20 employees. Smaller firms have been shown to have lower levels of productivity and are slower to adopt new technologies than larger firms.

- Small firms also lose efficiency because of the lack of economies of scale.

- We are not embracing high tech business solutions. “Canada has been a laggard in adopting information and communication technology (ICT) and meaningfully slower growth within this area explains much of the growing U.S.-Canada productivity gap in the two decades prior to the pandemic.”

- Climate change is driving inefficiencies by forcing companies to adopt technological changes that don’t necessarily improve productivity.

Pro’s and Con’s of Proposed Solutions

OK, so we have weakly connected businesses, spread across a vast country. We have a history of being “hewers of wood and drawers of water”, selling raw materials to others, primarily the Americans, who then add value through refining, manufacturing etc. We’ve been slow to modernize our businesses and we’re not doing a good job of investing in business improvement. How do we change all that?

Ms. Rogers, from the Bank of Canada, says there are two basic strategies for doing it. “One is to have the economy focus more on the industries that add greater value than less-productive activities. The other strategy is to keep doing the jobs we’re doing but do them more efficiently.”

Getting More Tech in the Economy

I want to tell you a short personal story about that “add greater value” proposition. In 1974 I came out of university with an Honors Chemistry degree and started work at Diagnostic Chemicals Ltd in Charlottetown. DCL was founded by Dr. Regis Duffy, who was, at the time, the Dean of Chemistry at UPEI. We produced speciality organic chemicals for use in hospital laboratories. It was definitely a “start-up” company. Housed in an old abandoned automobile garage, I was doing chemistry in five-gallon plastic buckets with a Black and Decker drill clamped to the wall for a stirring apparatus. But that company had all the elements needed for productivity. I was, for a year or two, the only BSc chemist there – the rest were all PhD’s, so it was a highly skilled workforce. We were producing complex chemicals that sold at very high prices, so the “value added” was significant, and the transportation cost which is such an impediment to most industry in the Maritimes was insignificant. Dr. Duffy drove capital investment, exploited government incentive grants, and expanded the company quickly. By the time I left the company in 1979 to join Ontario Hydro, the company was housed in two new buildings in an industrial park in Charlottetown. The business developed two main streams – one was the production of chemicals and the other focused on enzymes. Staffing for this little business peaked at about 180 in 2012. In 2007, one half of the business was sold for $57 million. In 2013 the remainder of the business was sold for $50 million dollars with performance clauses that had the potential to increase the final price to $100 million.

The cynics amongst you will no doubt point out that the company really took off after they got rid of me. But I think that we need more of that model in the Maritimes – high tech or niche industries where the disadvantages of distance can be overcome by capital investment, specialization and investor boldness.

The need for higher value products means that we need to strategically incentivize investment and growth in high tech goods and services industries. We really need to identify high value products that can be produced by a dispersed Canadian workforce.

The immigration Puzzle

Immigration policy is part of the solution. Developed countries, including Canada, currently have older populations and lower birth rates than the underdeveloped world. Canada’s birth rate is among the lowest in the world. It’s well below the “replacement rate” so, unless we welcome immigrants, we’re going to grow older and slower and less productive. And being less productive as a nation means that we all grow gradually poorer.

There is currently a world-wide and very short-sighted opposition to immigrants. In fact, some countries are fighting to close their borders while at the same time trying to pay “native” women to have babies. There’s only one way to see those contrasting policies, and that is that it’s a racist view of the world. We’d like more babies, but not brown or black babies. I hate to burst your bubble, but demographers tell us that most of the population growth between now and the end of this century is going to be driven by Africa. We’d better drop our colour consciousness. Matching skills and credentials to employment needs, not skin colour, must drive Canada’s immigration quotas. We must continue to encourage immigration, and we need to get better at recognizing and using the credentials of highly skilled workers who come to these shores.

The Down Side of Immigration – Housing.

Those immigrants need housing, medical care, and other services that Canada is currently struggling to provide for the existent population. Some have argued to me that we need to put solutions for the housing crisis and the medical system burdens in place before we allow more immigration. My view is that that won’t work. We’re never going to solve that problem before it shows up. Bring those people here and put them to work, and then put other people to work resolving the problems that are created.

The down side of that is that it will generate significant demand in our least productive sector – residential construction. And that one requires the second approach to productivity – we need to get better at building housing. In addition to speeding up the zoning and building permissions process, we need to harmonize and modernize building codes across the country. For example, in Sweden, the building code doesn’t tell you how thick the drywall has to be. It tells you how long it must hold back a fire, and the builder must then demonstrate that his design and materials meet the requirement. The modern building code coupled with innovative approaches to housing construction is changing the housing landscape in Sweden. Swedish housing is moving towards industrially produced modular homes, with 45% of housing being “industrialized”. Similarly, in Japan, nearly all construction is now industrialized.

Fostering Competition

The Bank of Canada, and the TD Bank, and the University of Calgary would all like to see a more competitive economy. Competition spurs innovation, drives investment, and produces productivity gains. All of which sounds good.

But what happens if, for example, we open up our borders to Verizon and AT&T and Comcast and other major players in the US telecommunications industry? Well, we would likely see internet and cell phone data costs sharply reduced, which would seem like a good thing. We’d also likely see crippling impacts to Rogers and Bell and Telus and job losses would be almost certain.

What happens if local builders amalgamate into an “industrial” construction firm with a high-tech modular building format? Well, likely local jobs would disappear and workers would concentrate in larger centres to mass produce housing.

The economists tell us that the productivity increase (whether from from high tech, or from AI, or other innovation, or from increased competition) will, from a big picture point of view, result in more jobs and a higher national standard of living. However, if you’re the guy who lost his job at Rogers, or the lady carpenter who had to move to the city to work in a large-scale housing factory, you may not immediately recognize the disruption as a good thing. And therefore, when government incentivizes innovation and competition, they’re also going to have to look at things like re-skilling and relocation assistance, and they’re going to have to do a really good job of selling some disruptive policies.

Taxes

Taxation is definitely part of this puzzle. On the one hand I’d like to keep corporate taxes low so that businesses can compete on the world stage. On the other hand, I’d like the government to develop a national strategy for productivity increase and invest in that strategy, whether that is by incentives to foster investment, or by investing in some significant infrastructure upgrades (or likely both). If you think about the United States losing momentum owing to the madcap actions of the orange idiot who is, among other things, destroying research and development capability south of the border, then this challenging period is, like all times of challenge, a time of opportunity. The magic trick is going to be to tax just enough to meet the needs without crippling business growth.

Big Government or Small Government

I’m not afraid of bigger government. Some of the most democratic, happiest countries in the world, with the highest standards of living are among the most heavily taxed and sport sizeable government beaucracies. So, there’s nothing automatically wrong with a large government service. However, these economists have pointed out two drawbacks that I thought were interesting. First, government takes productive resources — capital and labour — away from the rest of the economy. You can’t be working in a high-tech industry if you’re counting beans for the government. Second, many things that governments do — such as providing infrastructure, publicly provided R&D and even health care — can have a direct impact on private-sector productivity, as they can act as a brake on competition.

Summary

Canada’s poor labour productivity is a problem. Failure to solve it will result in declining standard of living, declining availability of government services, and decreasing faith in our institutions and system of government. But the problem is very complex and the solutions are going to cause new problems. We are going to need to try to understand and interpret things from a big picture perspective. And I think we need a national productivity strategy that we can all understand and buy into.

***************************************

References

1) Bank of Canada Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers speech, March 24 2024.

“Time to Break the Glass: Fixing Canada’s Productivity Problem”

2) America’s Labor Productivity Sets it Apart

James Marple, Senior Economist, AVP TD Bank

Brett Saldarelli, Economist

Date Published: April 30, 2024

3) From Bad to Worse: Canada’s Productivity Slowdown is Everyone’s Problem

Beata Caranci, SVP & Chief Economist | 416-982-8067

James Marple, AVP & Senior Economist | 416-982-2557

Date Published: September 12, 2024

4) Productivity Growth in Canada: What is Going On?

Tim Sargent

University of Calgary School of Public Policy

October 2024

5) How an American Dream of Housing Became a Reality in Sweden.

By Francesca Mari

New York Times, June 8 2024,

10 responses to “The Productivity Puzzle”

Nice job summarizing a very complex but essential issue. For housing, when demand is significantly higher than supply, there is no incentives to become efficient. In short term governments need to step in to create more balance supply/demand. We also need a better environment for businesses to invest in R&D.

Thanks for the comment, Harland. I’m afraid, though, that I have to disagree. If demand is significantly higher than supply, that applies upward pressure on price. The resistance to upward pressure on price should be the incentive to become more efficient. In the current environment, a builder who was able to produce quality housing for 20% less, would make a bundle.

I agree that government has to step in to do something about the balance between supply and demand. This inevitably triggers the argument about government interference in the economy versus private enterprise. I think I’d rather the government invested heavily in incentives, grant programs, etc., then getting involved in directly building houses themselves.

And absolutely, the government needs to do something about making a better environment, environment for investing in R&D.

Harland’s rebuttal to my comment:

We definitely disagree. It has been a very long time since I got my finance/economic degree and knowledge has expanded greatly but this is my recollection

Your analysis is correct depending on the elasticity of the demand. If I own the supply where demand is far greater, there is incentive for efficiency, if and only if, someone can easily come into market. However if little competition and difficult for new competitors to come into market, you can charge almost whatever you want (especially for essentials like shelter, energy and food) without being efficient. In fact there is incentive to reduce quality to get more profit.

If demand is less than supply, prices will go down so I can sell my products and to keep making a profit, I need to get more efficient and/or improve quality at same price to differciate from my competitors.

My Response to his rebuttal:

You are right, sir, and I was wrong. I am confusing the incentive for government, or an innovative “disruptor” to get in and take advantage of the opportunity that is created by high demand coupled with competitors inefficiency, with the incentive for a current market participant to change. Current market participants are fat, dumb and happy and there’s no reason for them to change (unless they spot opportunity and become the disruptor).

Hi Denis,

As always, I truly enjoy your insights! Of course, it would be boring if we all agreed. You raise important facts, but it’s the interpretation of those facts where I have to respectfully disagree.

Let’s start with a minor point: climate change. Is it truly climate change itself driving up costs, forcing capital to flee to other countries, and decreasing productivity? Or is it the restrictive government policies implemented in the name of combating climate change that are responsible? I am fully supportive of protecting the environment, but poorly conceived policies are what unnecessarily raise costs and reduce productivity—not the changing climate itself.

You also mention government, but I feel you barely scratch the surface, and you note you’re not opposed to big government. Since 2015, the Canadian government has added over 100,000 full-time positions. Today, 4.4 million people are employed by the government, accounting for over 21% of the workforce—the highest level in more than 30 years. As you rightly point out, these roles are not contributing to productivity growth. Meanwhile, the government’s use of private-sector consultants has not decreased either. Although consultants are technically employed by the private sector, their work for government agencies does not boost productivity. In terms of public sector employment, Canada is now one of the largest among developed nations. For context, government employment in the U.S. stands at about 15%, making Canada’s rate roughly 33% higher—even before factoring in consultants.

Finally, a topic near and dear to me: natural resources and mining in Canada. Without question, this sector has been a major contributor to our GDP and overall national wealth. You correctly note that new discoveries are becoming harder—much of the low-hanging fruit has already been found. However, Canada still holds tremendous mineral potential, with vast areas remaining relatively unexplored. The bigger issue is the dramatically increased timeline to develop a mine. What used to take around 12 years now often takes 18, and sometimes over 20 years. As a result, Canada—once a world leader in mining—is now among the slowest jurisdictions globally. This has led to a shift in capital flows toward resource development in other nations. The world urgently needs new mineral supply, and yet it is increasingly difficult to raise exploration funding in Canada, despite its high geological prospectivity. What caused this decline? I don’t know for certain, but I suspect that the growth of government bureaucracy plays a significant role.

Hi Brian. Thanks for the comment. I always enjoy a good exchange of ideas.

Let me start, as you did, with the climate issue, on which I offer a couple of perspectives. First, yes, climate change, all by itself, is driving up costs and limiting productivity. When we spend all summer fighting wildfires, we’re investing labour in a product that produces no revenue. Three years after hurricane Fiona hit the Maritimes, we’re still cleaning up – again, a necessary investment of labour in a process that generates no revenue. Current estimates for the insured damages – just the ones covered by insurance – are over $800 million. I could go on, but I’m sure you get the picture. Climate change is driving us into unproductive activities just to maintain a grip on what we’ve got, rather than increasing our prosperity.

Second, let me tackle your point about “restrictive government policies” vis a vis climate change. You state that you’re supportive of protecting the environment. If you agree that climate change is real and not just a junk science as proclaimed by the orange idiot, then we are obliged to do something about that. I’ve heard this process referred to as “transitioning to a post-carbon economy.” I don’t believe that we’re ever going to achieve zero combustion of wood, oil, gas or even coal. But I believe that transition to a post-carbon economy where those things are no longer dominant is necessary and in progress.

That transition is going to cost us. Nothing like that happens for free. I’ve made the point in previous writings that it is a bizarre, blatant and outrageous lie for Pierre Poilievere, Jagmeet Singh, Doug Ford, Tim Houston, Danielle Smith and others to proclaim that we’re going to fight climate change but “not on the backs of Canadians”. Ridiculous! Where the Hell else is the transition cost going to come from? Corporations? Corporations are held by shareholders who are Canadian. And Corporations will find a way to pass the costs along to consumers, or they will perish.

And finally, that brings me to regulations. I made the point in a recent article that regulations are the rules of the game. They are the framework inside which companies are invited to do business in Canada. I believe that the consumer price on carbon was good policy and that the industrial price on carbon is necessary and somewhat effective as well. But there are, no doubt, variations on the theme that would also help drive the transition to a post-carbon economy. So, if you want to argue that we should adopt different and better regulations, I have no problem with that. If you want to argue that we want to repeal all our climate regulations (“drill baby, drill”) then I would tell you that your support for environmental protection is sadly lacking in substance. We need rules to force the transition. Those regulations will inevitably impose costs. And I see no ethical way to avoid the obligation to accept our share of the global burden of the transition.

On the size of government issue, I think we are in violent agreement. Government growth in the Trudeau era was excessive. I’m hoping that the next Prime Minister (presumably Carney, according to the polls, but whoever) finds a way to rein in the growth of government. The relationship of the size of government to the productivity issue is interesting though. If we were a more productive country, we’d have more national revenue, and it would be easier to re-distribute income to support social programs like better health care. If we solve the productivity puzzle there will be a tendency to look at our social safety net and say “we can do better”, which will put upward pressure on the size of government. But right now I think the focus of government really needs to be on the productivity puzzle, which is, by the way, fundamental to surviving the Trump trade war and the 51st state threat.

I think we’re mostly in agreement on the regulations issue as it pertains to mining also. In the article, when I talked about the reasons behind the low capital investment rate in Canada, I noted that “a third component of corporate reluctance to invest heavily is a regulatory approval process that can be both lengthy and unpredictable.” I didn’t address that specifically to the mining industry, but it was certainly front and centre in the papers I read as a general issue. The Economist has had an article or two on the multi-national push-back against excessive regulation, and I think it’s a good thing. As with climate change reg’s, the trick is going to be to eliminate regulations surgically. I think we can change rules. I don’t think we can eliminate the concept of a rulebook.

Hmmm.It’s not hard for me to play dumb, but may I be dumb with a purpose here? So, may I begin by asking, what exactly is “productivity”? How is it defined? And how is it measured? What kind of self-serving construct is it? Does it distinguished quality from quantity? Monetary value from societal value? Canadians being 71% less productive than Americans sounds like a chemical equation or an engineering calculation about how much load a specific material can bear. But it isn’t. It’s a number generated from human behaviour.

And once those questions are answered, I would tentatively posit that increasing productivity — even if that is a desirable goal — defies easy solutions in the same way that it defies easy definition. And it especially defies easy, one-size-fits-all solutions, since “productivity,” whatever that is, is entwined with so many other factors that it is hard to separate it from them. e.g. Is productivity linked to workplace satisfaction? Is it tied to other cultural values/trends/attitudes? Does it trump other indexes of societal health? Does it trump quality of life (something else that people are currently trying to measure)? Is what’s good for Alberta good for New Brunswick? The eminent U of M economist Donald Savoie argued a few years back that federal govt employees in Atlantic Canada should be paid less, since federal bureaucracy was sucking talent away from the private sector where it could be growing the economy, innovating, etc. You know what the result of that would likely be in Atlantic Canada? People leaving to work for the feds in other, better-paying parts of Canada. The bloated federal bureaucracy in the US is being gutted. What will the effect of that be? It will ripple through the entire American economy, as tens of thousands of consumers lose the incentive and ability to consume.

Finding formulas for human activity is always a tricky proposition. “Experts” used to argue in the 19th and early 20th centuries that southern Europe was economically backward because they were predominantly Catholics and kept taking time off from work because of all those holy days and feast days. They were, in a word, lazy. Perhaps. Or perhaps that was a value judgement rooted more in religious bias than economics. Other productivity arguments were rooted in racism — and still are. But part of it comes back again to definitions and calibrations. Apparently it’s not the number of hours worked but some calculation of “value” produced from the measured inputs of labour. Hmmm.

Hmmmm indeed. It’s probably unworthy of me to suggest that this comment from a native of PEI shows a degree of defensiveness about the dismal productivity statistics from the Maritime provinces. There are, I believe, some very specific reasons why the Maritimes have problems with labour productivity, and they have to do with distance from markets, low prices on the primary products of those provinces, and perhaps the “small company” nature of Maritime industries which doesn’t do well, statistically, at fostering innovation (DCL and Biovectra being a notable exception). I hasten to assure you that it has nothing to do with being lazy, as the nature of the metric corrects for hours worked.

Productivity is a purely economic measure. If I defined it as GDP divided by hours worked, I would likely be wrong, but I’d be close. As such, (and I know you know this) it is not a measure of quality of life or job satisfaction or populace happiness. But in the long run, if we don’t turn the ship, it will impact some of those things, because we won’t be happy with the declining standard of living that goes with sub-par productivity.

It’s a simple enough concept. The more the world values what we produce in each hour that we work, the better off we will be. And, as we engineering and science geeks say “what gets measured gets managed”, so economists in their imprecise and difficult science are trying to measure it as best they can. To quote one of my source articles “measuring productivity is not as easy. While it is relatively straightforward to calculate total hours worked in the economy, through survey or administrative data, measuring real output is much more complicated. The usual approach is to calculate the output of an industry or economy in actual, nominal dollars, and then use a measure of prices to convert output in a given year to what it would have been in a base year at the prices of that base year… While calculating price changes for standardized commodities such as a barrel of oil or a pound of butter is straightforward, calculating prices for goods like cars is not, because their characteristics are changing. While cars are more expensive than they were a generation ago, they are also more fuel-efficient, safer and are packed with electronic gadgets. Once prices are adjusted for this increase in quality, it is not at all clear that they have actually risen. The job of statistical agencies gets even harder when new products — such as smartphones — appear, with no historical price data at all. Harder still are services like social media which are often provided for free, and thus have no price to measure. Although there are ways to address these problems, it is quite likely that measures of real output, and thus productivity, are imperfect, to say the least.”

“Ahh,” you say, “they’re guessing at a lot of it.” But I’m sure that they’re guessing at it in the same way for every country and from province to province. They agree a convention and apply it uniformly and that will make a lot of inaccuracies cancel out. I think we’d be wise to accept that when they tell us we’re falling behind the rest of the developed world, they’re right. And much as you might dislike the message, when they say that the Maritimes are lagging in productivity, they’re simply saying that the Maritimes are tough places to make a good living in. And you absolutely know that to be the case. We can either accept that young people will continue to leave PEI, or we can look for ways to get more efficient either through producing new and more high value products, or by being more efficient about how we grow potatoes and catch lobsters.

One of the things I noted in my article is that solving the productivity puzzle is likely to bring about some unpleasant disruptions. One of the logical consequences of productivity improvement policies might be the further growth of corporate farming and the consequent death of the family farm (I think it’s largely disappeared already). We might see a tendency towards larger production facilities with more people moving closer to big cities. We could reject those trends because we value our rural way of life more, and the ballot box will let us do that. But I just think it’s important that we understand the link between productivity and standard of living, national debt, resilience to inflation and other such economic ills.

Brian Main comment #2

Thanks for your reply. It is so hard to keep up (I think I still “owe you” a reply via the carbon tax debate I never got to last year, so I am trying to reply quickly this time lol!).

Its not always easy to interpret what one is saying (be it me or you) by the written or spoken word for that matter. I believe this may be the case with climate change as I know we have respectively different views on this with respect to Canada’s actions. Not belief in science, not drill baby drill, but tipping of the pendulum too far in one direction, which is always a subjective opinion and where I feel we have definitely taken the wrong decisions that has put us behind others.

The question on productivity is primarily the discrepancy between our productivity and other Nations. I have to respectively point out that while climate change does have negative productivity implications (although in a rebuild phase later on, disasters can somewhat help GDP, although overall I agree it tends to have very negative consequences) your point is misdirected as it does not address the question in discussion – why is Canada’s productivity so far behind others? Look at the fires in Australia and California – they had way larger an impact on those economies than did the forest fires in BC on Canada. Further, for less developed nations, disasters are usually more profound on productivity than in developed Nations. Essentially climate change impacts all nations globally, most far more than Canada. Given that fact, one has to conclude than that if your argument is climate change is impacting our productivity more than others, than the primary difference between Canada and the rest of the world, is our policies (which we know our divergence of thinking there).

I do agree with you that government regulation is of course an absolute necessity, it is over-regulation that decreases productivity, and this is what I believe has contributed to Canadas demise in productivity, whether it be delaying energy and mining projects (effectively cancelling them and forcing capital to go elsewhere) and or increasing energy costs (through forcing inefficient (non productive!) energy solutions such as windmills down our throats, but that is another topic to debate…

I look forward to reading your next curly cues as the topics always seem to be near and dear to most!

Cheers,

Brian.

Brian, don’t worry about the carbon tax issue. It was good policy. Poilievre lied about it and sold the big lie. Carney did the only politically safe thing to do, and got rid of it. Case closed.

Now, the rest of the story….

I’m not sure that I have argued, or would ever argue, that climate change is hitting us harder than others. I think climate change, in and of itself, even if we’re not trying to do anything about it, is having a productivity impact. I agree with you that the degree of regulation is going to impact on the productivity puzzle. Fundamentally, the countries that are trying hard to defeat climate change are going to take a productivity hit and fall behind countries (like Trump-2 USA) that choose to ignore the issue. How much of a hit we take I guess depends on how seriously we regard the climate change threat.

I think it’s important not to get too absorbed in the climate change portion of the problem. Our declining productivity traces back 50 years. The first impactful climate change regulation was issued (by Alberta of all places!) in 2007. East-west infrastructure linkage, smart de-regulation, regulatory harmonization, tax policy, labour mobility, R&D incentives – we need them all, irrespective of climate change.

Dennis,

Absolutely, I’m defensive. Guilty as charged. On the other hand, our quality of life index is much higher than many other places. . .

You do a capable job of outlining the cost of not increasing productivity. I wonder what the cost will be — in those intangible, hard-to-measure areas — of increasing productivity?

We do find common ground in advocating the same economic strategy for Atlantic Canada. Conventional wisdom mantras for success in business talk about the advantage of being the first, the best, or the only. Except when it came to the silver fox industry, PEI couldn’t capitalize on all three. But the antidote to a producer who can’t compete on volume or price is, indeed, to create value-added products that people will pay more for, off-setting the disadvantages of scale and distance from markets. DCL did that, although it was a little harder and more complicated than we make it seem. The seed potato industry for many years was able to do that, too, when we could tout quality and disease-free status. Our oysters also compensated for distance through quality/taste — until, twice now, we imported lethal diseases in an effort to . . . increase productivity. Nevertheless, I’ve been preaching that value-added strategy for years to my PEI classes. But I never couched it as “productivity.” Rather, I called it competitive advantage.

Thanks for generating so much good discussion.

Thanks as always for your comments Ed. It is I who should be thanking you for for generating so much good discussion.