You may recall that, in my last essay on the mind and musings of Mark Carney, I wrote about his view that we need to place a value on resilience. One specific aspect of that resilience was to expect and prepare for the next pandemic, so that we’re more ready the next time than we were in 2020. You may also recall that in my second last article, (the one on Doug Ford), I gave Ford credit for dealing fairly effectively with the Covid epidemic. In those stress-filled months of 2020, politicians of all stripes, and Doug Ford in particular, swore that we’d never get caught with our pants down like that again. All of which prompted me to wonder whether we actually did anything, or was it all sound and fury, signifying nothing? What I found is encouraging (if you’re an optimist), but infuriating if you’re a fiscal conservative.

You’ll be happy to learn that governments have done what governments do. They’ve passed new laws. Ontario, for instance, passed the Pandemic and Emergency Preparedness Act, 2022. That Act is something of an omnibus bill, which makes amendments to a number of other pre-existing bills to add in emergency preparedness requirements. Sensibly, the government took a wide scope approach and tried to anticipate what might be required in any type of emergency and not solely in pandemic emergencies.

Every government department, board, agency – whatever – is required to “identify and regularly monitor and assess the various hazards and risks to public safety that could give rise to emergencies.” Such assessment includes the obligation to identify “goods services and resources” needed to address the public safety risk that you’ve identified, and to do a gap assessment so that you create a shopping list of things that you should have on hand to combat that identified emergency risk.

Each responding department forwards that assessment to the Chief of Emergency Management Ontario where they are assembled and coordinated into the Ontario Emergency Management Plan. With a plan in place, the Solicitor General is then mandated to conduct training programs and exercises to ensure that when the kaka hits the fan the plan can be executed effectively. There is a requirement to report annually on progress made in emergency preparedness and a requirement to review and revise that plan at least once every five years.

Some specific requirements that I found interesting & encouraging include:

– the Minister of Agriculture is required to report on the safety and stability of Ontario’s food supply, and in addition

- the Agriculture Minister must have a back-up to effectuate food distribution if the Ontario Food Terminal facility were to be unavailable for up to thirty days.

- the Minister of Government and Community Services must create (and report on) a supply management plan addressing the personal protective equipment and critical supplies and equipment required to address all the potential emergencies that are identified.

- Every long-term care home in Ontario is now legally required to conduct annual exercises (such as tabletop simulations) that mimic a pandemic or infectious disease outbreak.

Ontario seems to have the lead in these emergency preparedness developments, but other provinces are following suit. I looked up and read through the Ontario legislation. I haven’t tried to do that for every province. Google Gemini (my AI researcher of choice recently) tells me that BC, Alberta and Quebec have passed pieces of legislation that mimic the Ontario Pandemic and Emergency Preparedness Act. Commonly the legislation addresses “centralized supply chains, mandatory risk reporting, and inter-jurisdictional coordination.”

The Federal Government has gotten into this act as well, passing the Pandemic Prevention and Preparedness Act (Bill C-293) which became law in 2025. That law sets up a coordinating office to ensure that provincial stockpiles and surveillance systems are interlinked. It also establishes a two-year reporting requirement which places an expectation on the lower jurisdictions to report on their emergency preparedness at least biannually.

And what about the other, smaller, provinces? Well, I have good news and I have bad news. The good news is that other provinces have not chosen to pass statutes but are simply upgrading regulations under existing legislation. So, they’re not totally being left behind. The bad news is that they’re not making great progress. For example, the Auditor General of New Brunswick reported in 2025 that “while the province accepted recommendations for emergency prep, progress has been slow, with many departments failing to meet even the basic existing requirements of the Emergency Measures Act.”

Meanwhile, Manitoba and Saskatchewan are clearly feeling pouty about being told what to do by the Feds. Manitoba has started a review of their Covid response but explicitly stated it would be “limited” because “Manitobans have moved on.” And Saskatchewan’s readiness response is focused on trying to get a single software system to track staff and supplies across the province—but this software implementation process is struggling with data errors.

So we’re making plans. Good. But how are we doing at executing those plans?

I recalled from the high-stress Covid days that the Trudeau government highlighted the need to become less reliant on the rest of the world for vaccines. How’s that going?

The answer is, that’s going pretty darn well. The Moderna facility in Laval, Quebec which is capable of producing 100 million RNA vaccines does a year is now licensed and operating,. There’s an NRC Biologics Manufacturing Centre in Montreal being used for small-batch clinical trial materials and technology transfers. Sanofi, in Toronto, is producing pediatric vaccines for pertussis and diphtheria and after some start-up delays and setbacks is now in testing phase for the large scale production of influenza vaccines. British Columbia has a company called AbCellera which is building a massive antibody and vaccine biotech campus, and in Saskatchewan at the University of Saskatchewan, they are working to establish Canada’s first “Containment Level 4” vaccine lab. I mustn’t fail to mention that in PEI, Biovectra (a company which grew out of Diagnostic Chemicals, my first ever employer), is producing RNA products and expanded their production capability in 2025.

And those are just the highlights. In total the federal government has funded some 32 major life sciences projects, and provincial governments are also contributing to this thrust. At this point, total Federal investment is estimated to be $2.2B, with the provinces contributing about $1.9B. And of course, on top of the government incentive money is the actual health sciences companies’ investment which is estimated to be between 3 and 4 dollars committed for every government dollar invested.

It’s not all good news, of course. One company in which we invested heavily (Medicago) collapsed, and start-ups in the Sanofi business in Toronto have been significantly delayed. But I think we can feel a lot better about vaccine supplies now than ever before.

Going back to the Ontario legislation, I have to admit that I was impressed. It seems pretty comprehensive and well thought out. I started by reading the Ontario Ministry of Health reports from 2022 and 2025.Those reports are not primarily what I would call progress reports. They are directional in nature – defining key response areas and plans. They speak to things like:

– the need for better Public Health communication especially within disadvantaged minority communities.

- the need for database linkages to vaccination records for all groups.

- the decline in vaccine uptakes and it’s negative consequences for health.

- the avoided treatment and hospitalization costs associated with vaccination programs.

- the need for coordinated personal protective equipment availability, critical equipment supplies, laboratory services, vaccines etc.

You won’t find any pimples or warts in those two annual reports. If you want to find the uglies, you take a look instead at the Auditor General (AG) reports. The AG’s report points out some significant problems. As I read the report I found myself shaking my head a little bit at the magnitude of the problem, but I also found myself feeling considerable sympathy for the people at the pointy end of the stick.

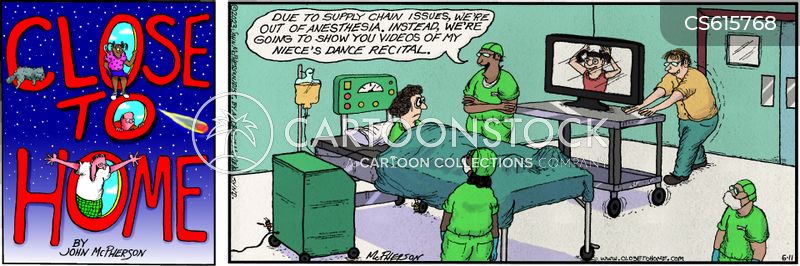

It all stems, really, from the Covid pandemic days. About 80% of Ontario’s stockpile of protective equipment (PPE) was found to be past it’s shelf life when the epidemic started, and we burned through the remaining supply in the early days of that crisis. So then Ontario went on an emergency purchase blitz, foregoing normal due diligence checks and paying inflated prices to meet the demand. China sold us a million N95 masks that had to be dumped because they didn’t meet standard, and various dubious suppliers flooded the market with “counterfeit” N95 masks. At least $66 million worth of hastily purchased product was dumped almost immediately because it failed to do the job. Stung by early procurement failures, and driven by the need to ensure supply of desperately needed PPE, the province entered into a number of long term guaranteed quantity contracts.

In 2023, the government created Supply Ontario and gave it the task of owning and managing the PPE stockpile. And to be blunt, this organization inherited a pile of crap.

Think of the stockpile as a big tank with an in-flow pipe and an out-flow pipe. You’d like a big stockpile so you’re ready to handle a big-sized emergency. But the stuff coming in through that inflow pipe comes with an expiry date on it, so it can only spend limited time in the tank. And how long it’s spending in the tank is determined by the outflow, which is PPE consumption rate. To complicate that scenario, not every item has the same shelf life – they expire at different rates. To make the problem more difficult, they don’t really control the inflow rates because in the height of pandemic pressure the province committed to long term contracts with suppliers in order to guarantee a supply chain.

Supply Ontario came up with the right answer. We need to keep buying this stuff in order to maintain the stockpile we swore we’d keep ready for the next emergency. And we need to use it up before it expires or it gets wasted. So let’s give it away. Hospitals and nursing homes need this stuff and the cost of medical care is killing us anyway, so this should be a welcome savings, right?

Not right.

The auditor General reports that only 2 to 3% of hospital PPE comes from the notionally free Supply Ontario stockpile. For surgical masks specifically, they were able to usefully deploy about 21% of the surgical masks they were bringing in, with around 40% of the masks going to long term care homes as opposed to hospitals. Not that there’s anything wrong with the long term care homes getting masks – the question is why are hospitals not lining up for “free” masks and all the other “free PPE” categories?

Part of the answer lies in those long term contracts signed in 2020/2021. We committed to a large number of Level 2 masks, but hospitals now consider them inadequate, preferring Level 3 masks. So we’re buying level 2’s at a committed pace far exceeding the demand. We’re also buying N95 masks, and they are in demand, but nowhere near at the level that we’re buying. In 2025, Supply Ontario was only able to distribute about 22% of the N95 masks that they bought.

The second part of the answer is that Supply Ontario is not as good as the private contractors at supplying what the customer wants. Supply Ontario products meet Health Canada standards, but do not “always align with hospitals’ procurement preferences or requirements”. So although you can get a glove or a mask or a boot cover, you may not be able to get the ones your doctors like to use. And even if you can get what you want, you may not get it promptly. The auditors tell us that Supply Ontario has about a nine day average order fulfillment time. The private sector gets it there in 2 to 4 days.

Those private sector suppliers have been working with hospitals for years, and they have contracts of their own to worry about. So the hospitals are telling the auditors that while “free” sounds good, we trust our present suppliers to get us exactly what we want, when we want it, and Supply Ontario doesn’t give us the same warm fuzzy feeling, so piss off.

Well so what? Is this a big deal?

I’m glad you asked, because some of the numbers are eye-popping.

- Ontario wrote off $1.4B worth of inventory between 2022 and 2025.

- The fixed purchase contracts will likely lead to 376 million surgical masks and 96 million N95 masks expiring and being trashed over the next five years, costing us a further $126 million.

- Some 350 million items of expired PPE are clogging up about 20% of Supply Ontario’s warehouse space.

- In the last two years we disposed of 780 million PPE items at a cost of $16.8 million. Most of that disposal was done through a “trash to electricity” incinerator, so at least we get some energy out of the process, but the auditor points out that it’s pretty expensive electricity and it comes with a greenhouse gas penalty.

Ontario, as the most populous province, has the biggest problem in terms of those eye-popping numbers. But all the provinces are experiencing similar problems in converting from a static stockpile (full of items subject to expiration dates) to a revolving-door inventory management system that meets consumer needs while still maintaining a reserve supply.

My AI helper summarized thusly “The most striking similarity across all provinces is the resistance from hospitals. Auditors in Ontario, B.C., and Alberta all found that hospital procurement managers are protective of their autonomy. They often view provincial stockpiles as “emergency-grade” (lower quality or generic) and prefer to maintain their own private contracts for “daily-use” (higher quality or specific brands).”

I don’t regard all of this as a really bad news story. Waste and government inefficiency are always newsworthy stories, and this one makes me blink a little. But it’s a Hell of a task to organize a province wide distribution system with up-to-date inventory control and mandatory stock rotation.

When I started to look into this, I rather expected to find that, now that the pandemic is over, governments would be shrugging their collective shoulders and addressing other problems. So what I found was that we’re in there giving it the good old college try and messing it up totally. Well making mistakes, even big ones, is better than doing nothing. There’s a chance we’ll get this right eventually, as long as we keep working at getting better.