In the aftermath of the Federal election, there was much discussion of voting patterns, and how the NDP and the Bloc both lost seats as a result of the divisive nature of the campaigns. There was a general consensus that a lot of people voted “against” Poilievre, or “against a 4th Liberal term” as opposed to for the party they really wanted. That led me to thinking about election system reform.

When you look at some of the data from the election results, there is little doubt that Canada’s democracy is not at all well-served by the current election system. Liberals received 43.7% of the vote and won 49.6% of the seats. Conservatives received 41.3% of the vote and won 42.6% of the seats. The NDP with 6.3% of the votes, got only 2% of the seats. The others, (Bloc, Greens, independents) got 7% of the seats with 8.7% of the vote.

The major parties got more seats than their votes would justify and the minor parties received fewer seats than their vote share would justify. The discrepancies aren’t huge, and you might look at it and say “it doesn’t matter”, but I assure you it matters to the NDP and the Bloc.

Digging a little deeper into the numbers provides more evidence of the problem. In the “first past the post” (FPP) election system that we’re running, only 57.3% of elected MP’s are going to enter Parliament with an actual majority. The other 42.3% have a cushy MP job despite the fact that more people voted against them than voted for them. And that stinks.

Furthermore, in this election, according to many surveys and interviews that I’ve seen, many voters who have been traditionally NDP supporters, voted for the Liberals or the Conservatives because they thought it was important to block the other major party. There were a number of blue seats that turned red because NDP sympathizers voted strategically to avoid Liberal/NDP vote splitting. There were some orange seats in the St Catharines and Windsor areas that I think turned blue because Poilievre attracted autoworkers disenchanted with the Trudeau government who were determined to defeat the Liberals, and who knew that the NDP would not form government. So, some people are feeling constrained about their choices – unable to vote for what they really want because of fear of what that vote might allow.

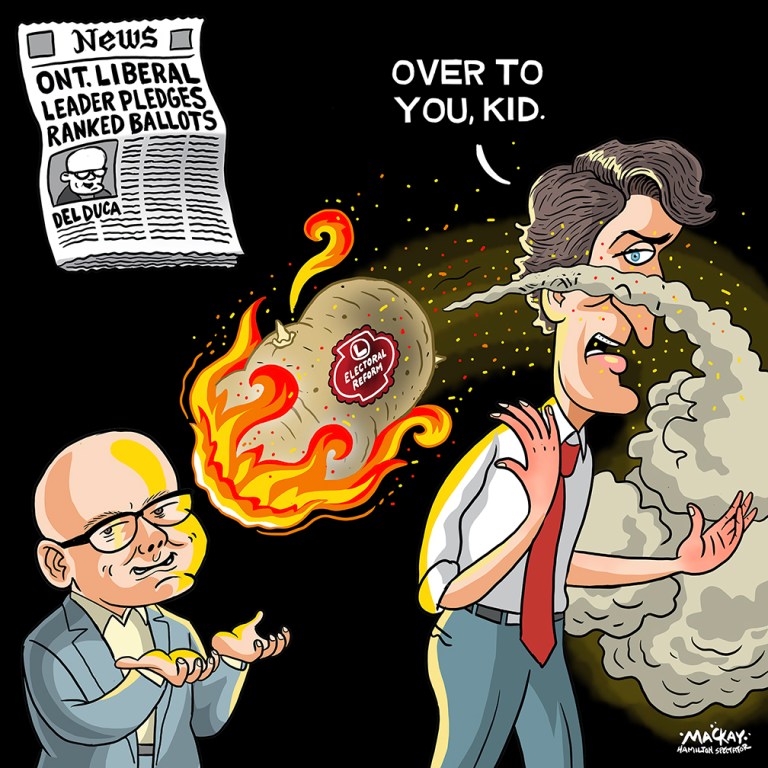

Electoral reform, promised to us by Justin Trudeau in 2015, has the potential fix all that. Well OK, it might fix most, not all, of it because no system is perfect. But I think it is well past time we did something.

It’s not like we have to invent something new. More and more jurisdictions are turning against FPP election systems. Australia, France, Ireland, Scotland, Brazil, Chile, Peru, Malta, Senegal and Nigeria all run alternative election schemes successfully. That, by the way is not an exhaustive list by any means – I just think it’s a long enough list to show you that both old established democracies like France and Australia and some less developed democracies like Chile and Nigeria are using better systems than us. Even the failing democracy to the south of us is improving – Maine, Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana and Mississippi are using run-off elections for state level elections.

It is interesting to see how many different systems (and variations of systems) are being used. One system is a run-off election system. In a multi-candidate election, if no candidate achieves 50% +1, the lower level candidates are dropped from the ballot and voters are asked to vote again. At the end of the day, if you can’t elect what you’d prefer, you can at least elect someone who is acceptable to the majority.

There are three or four problems with this system. First, it’s an expensive way to run an election. Second, it’s time consuming, and doesn’t produce an immediate result. Third, the turn-out for the second-round run-off is rarely as good as for the initial balloting.

One of the advantages of the run-off election system is that it reduces the divisiveness of election campaigns. Candidates who need to appeal to voters for whom they might be the second option have to be careful not to alienate those voters. And that brings up the last disadvantage of the run-off election, which is that when the campaign is reduced to two candidates, they are free to slag each other indiscriminately and to make desperate promises at the last minute.

An alternative to the run-off election system is the “instant run-off vote” ballot. In that system, the voter ranks the candidates. If no candidate receives a majority of first-preference votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed based on voters’ next preferences. This process continues until a candidate wins a majority.

There are, of course, variations on that theme and different ways you could declare a winner. In some jurisdictions you may rank all of the candidates. In others you might be asked to rank your top three or four. In some jurisdictions, points are awarded to each level of vote. In some points system situations, it would actually be possible for a candidate with a majority of first place votes to lose to a candidate with less than 50% first place votes but a great number of second and third place votes. If the points awarded to each vote are weighted heavily in favour of first place votes, the system looks more like the current system where a weak plurality is all that’s needed to be elected. If the system is weighted towards second and third place votes, then either a majority or a strong plurality is likely required to win.

Those run-off systems and variations are all aimed at electing a single candidate in one riding or electoral district. The other major approach is for proportional election systems where the desire is elect a number of candidates where the selection of candidates is broadly representative of the electorate’s choices.

Instead of dividing Canada into 343 ridings, we might divide it into 34 ridings with 10 candidates being elected from each riding. You’d then deploy something called a Single Transferrable Vote ballot in which voters would rank candidates. A quota would be established (there are rules on how to establish the quota) and if a candidate exceeded the quota he would be elected. Let’s say that 10000 votes were needed to be elected and candidate X received 15000 first place votes. 5000 votes would then be transferred to the second-choice candidates on those ballots. The process of transferring ballots to lower ranked candidates continues until ten of them are elected.

That process of transferring surplus ballots is vulnerable to corrupt election officials (who decides which ballots get transferred?) so there are methods in place to make those selections fairly. There are also variations on whether all candidates are on the ballot, some candidates are on the ballot and some are chosen from a party list, or all candidates are chosen from a party list. All variations on that theme are designed to elect candidates in close proportion to the distribution of voters’ choices by party. The variations have lots to do with whether the voter or the party is choosing the actual elected official.

I think the proportional voting model works well for larger and denser populations. I don’t think it would work well for Canada. PEI, for example, has 4 MP’s. Including PEI in any larger grouping of proportionately distributed seats would almost guarantee that for the first time since Confederation, PEI would wind up with fewer than 4 MP’s, and possibly zero. Geographically huge but sparsely populated ridings like those in Canada’s north would not be well served by proportional representation systems, no matter how candidates are chosen or vote counting systems are run.

I like the idea of Instant Run-off Voting. Each riding then elects an MP, and the electorate, not the party machinery, makes the final decision. The voter gets to name the person he or she most wants to represent them and the voter has a pretty good chance of getting a representative who, if not the favourite, is at least acceptable to them.

I think IRV elections would help eliminate the extreme divisiveness that has infected the United States. I think Pierre Poilievre’s nasty approach to politics over the last 3 or 4 years was rejected by the electorate on April 28th, and I believe that an IRV system would force him, and other like him, to be more moderate in his language and behaviours.

No system is going to be perfect. I know there will be voters who still try to game the system, and so the final rules about how many ranking choices you get, how the votes are counted and/or eliminated need to be carefully chosen. But in the final analysis, we’re currently using a 19th century voting system and it’s resulting in elections that are unfair to the smaller parties, and unfair to voters in that results don’t reflect accurately what the voters really want. A new system is badly needed.

Wow, you might say. Too damn many options, and too complicated. Who’s going to decide what’s best for Canada? The first answer is “not a political party”. Or at least not at the start. They are much more concerned about what’s “fair” (meaning advantageous) for their party than they are for the voters.

The second answer is “not the general public”. Much as I love democracy, public opinion surveys where you ask people for their recommendations about a subject about which they know little or nothing, are unlikely to produce a useful result.

The right answer, in my ever so humble opinion, is academia. All of these systems are part of something called political science. There are people who are experts in this. The government should create a panel of Political Science experts to propose a new system for elections. The government of the day should then propose a bill to bring the new system into being. Democracy will get its chance when MP’s vote on it. And if we’re really lucky they’ll ditch their partisan positions and adopt a system that works for all of us.

One final note – in Pierre Poilievre’s riding, there were something like 91 names on the ballot, with most running as independents. The “long ballot” was organized as a protest by the Longest Ballot Committee, which is pushing for electoral reform. I’m relieved to find that if all of the votes awarded to these silly candidates were awarded to Poilievre, he would still have lost. I may want election reform, but this is the wrong way to go about it. Elections aren’t a game. Elections Canada should consider hiking the candidate deposit to a level that discourages trivial candidates.

2 responses to “Voting for Progress – and Vice Versa”

Hi Dennis. As you know there has been considerable debate on PEI over electoral reform over the past two decades. There have been two non-binding, free-standing referenda [with low turnouts and a unreasonably high bar of endorsement in order to generate reform] and one referendum tied to a general election. The second of the free-standing referendum actually chose a proportional representation system, and the most recent vote garnered nearly 50% in favour of reform (again, the bar was set deliberately high, not 50% plus one).

I think the interest has been higher here on PEI because elections have often been extremely one-sided in terms of results but not popular vote. A party with 40+% of the votes cast has on occasion won 0, 1, or 2 seats in a 30 or 32 seat house.

The PR system voted on here involved a hybrid legislature with part of the House elected in the old first-past-the-post way and part of the house elected from a ranked list of candidates according to the party’s overall share of of popular vote. Rural Islanders weren’t keen on the “list candidates,” since they didn’t know how the list would be produced (party vote or backroom boys) and feared the list candidates would cater to urban elites, thus further disempowering rural PEI. The other major stated objection to PR on PEI was the risk of political “instability” through a prevalence of minority governments. (Think postwar Italy rather than, say, Iceland.) Whether that objection was sincere or spurious isn’t clear. Given the conservative nature of PEI, the level of support for electoral reform was, to me, quite surprising.

The simple fact is that first-past-the-post is probably now less common around the world that forms of proportional representation. Time for Canada to catch up, I think.

Thanks for the comment Ed. You credit me with a lot more knowledge of PEI’s flirtation with election reform than I deserve. I was aware that PEI had toyed with the idea – I didn’t follow the arguments and options and knew little about the results.

I don’t know that proportional representation would work for PEI at all in a Federal election. PEI could group four seats and try proportional representation for those four seats, but I doubt that any Tignish candidate would get votes from Launching and vice versa. I remain convinced that Instant Run-off Voting works better for Canada’s population distribution than the proportional systems.

I also think that the IRV system is less complex, more easily understood, and less vulnerable to manipulation by the major party back room boys than any proportional system.

Having decided that IRV works best for the Federal system, I would strongly recommend that all provinces do it the same way so that we have one easily understood and manageable voting system.